Conor McMahon, Reporter at Fora talks to Peter Oakes, Founder of Fintech Ireland about how automated financial advice is expected to shake up the wealth management sector

SO-CALLED ‘ROBO-ADVISORS’ already manage billions of dollars in the US, but they have yet to make their way to these shores.

Traditional wealth management has been largely untouched by the march of digital on this side of the Atlantic, and the sector is still overwhelmingly burdened by paper and admin work.

But not for much longer. Automated financial advice is already making waves in the UK, and Ireland could see a surge of robo-advice firms setting up shop in a bid to access investors in Europe.

Fora spoke to fintech expert Peter Oakes, founder of Fintech Ireland and a former director at the Central Bank, to get the lowdown on what exactly robo-advisors do and how they might shake things up in 2017.

What are robo-advisors?

Robo-advisors are basically online money managers or “investment intermediaries”, Oakes says. They offer financial advice based on an algorithm.

Users supply them with financial and personal information that they use to make recommendations on where to invest. In a nutshell, they offer low-cost financial advice.

“We all know that the biggest expense of a portfolio is all the administration,” Oakes explains. ”The thinking behind a robo-advisor is that there must be a large portion of people out there that actually just need very simple advice.”

Independent financial advisors take a big bite out of returns on investments in fees. Robo-advisors basically do away with that money trail.

What kind of advice do they give?

The user fills out an online form and the robo-advisor firm feeds that data into their technology. The robot uses that information to create an automated series of investment recommendations based on the user’s appetite for risk.

For instance, somebody close to retirement would be categorised as having a low-risk appetite, Oakes explains.

Based on the details furnished to the robo-advisor, it would most likely recommend that a user invests in money markets and avoids property ”because you really want your funds to be liquid because you’re coming up close to retirement. The same should apply in the case of equities, as there is greater risk there – and that’s want you probably wish to avoid when you are about to get the golden watch.”

The answer is no, but they still pose a potential threat to traditional wealth management firms and financial advisors.

Much like any industry that robotics and automation have affected – car manufacturing, media, customer service to name but a few – the humans won’t be completely wiped out, but their functions change.

“There still will always be a need for a human intervention from time to time,” Oakes says.

“Because it’s a regulated service, you’ll still have human interaction, especially if you’re lodging a complaint – maybe (the robo-advisor) has moved your money into the wrong fund even though you have proof of confirmation.”

It’s worth noting that the some users might be nervous about a complete lack of face-to-face interaction. A wholly automated experience might spook them from putting their trust in an algorithm.

“It may just be that the robo-advisor actually just gives advice and then leaves it to the individual to execute how they get that investment exposure,” Oakes suggests.

The benefits

The pros of robo-advisors outweigh the cons – on paper at least.

“If you look at your investment portfolio and you have a pension fund for example, even when you’re returning 5% a year, after the financial advisor starts taking out charges at the current rate, you’re probably only getting a 1.5% return on your money,” Oakes says.

“This is an opportunity to increase that 1.5% to maybe 3%, so you’re doubling your return.”

Who will they appeal to?

Oakes thinks robo-advisors will be targeted at people who are already involved in passive investments, like exchange-traded funds (ETFs), as these kinds of investment porfolios are easier for individuals to invest in without the need for financial advisors.

A robo-advisor would suit those types of investments because an algorithm can easily identify trends.

“There are tracker funds out there and they’re doing very well,” Oakes says. “You could set up a robo-advisor that predominantly puts people into tracker funds or recommends tracker funds.”

Robo-advisors will also appeal to anyone who is used to doing their banking online.

When will they come to Ireland?

It’s hard to say for certain, but robo-advisors are tipped to enter the market in 2017.

One of the possible motivations for coming to Ireland is access to the European Union’s investment management licence, MiFID, short for the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive. It’s the regulatory licence that non-banks use for investment management services.

A robo-advisor firm that wants access to EU member-state markets might look to set up shop here and avail of the MiFID directive.

“If you were an Irish investment adviser or wealth manager, there are threats and opportunities here – in equal amounts,” Oakes says.

What does it mean for the heavyweights?

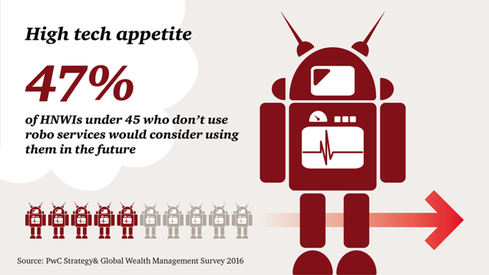

A recent PwC report suggested that traditional wealth fund managers are asleep at the wheel when it comes to robo-advisors.

It described the global wealth management industry as “one of the least tech-literate sectors of the financial services industry” and warned that it was falling behind non-financial services industry.

“Client expectations is sharply at odds with what’s currently being provided,” it said.

In her commentary on the report, PwC’s Olwyn Alexander said that the “sector is now acutely vulnerable to digital innovation from fin-tech newcomers, including robo-advice services” – and that firms that didn’t respond wouldn’t survive in the medium- to long-term.